Let us praise (again) Robert Irwin and his Central Garden at Getty

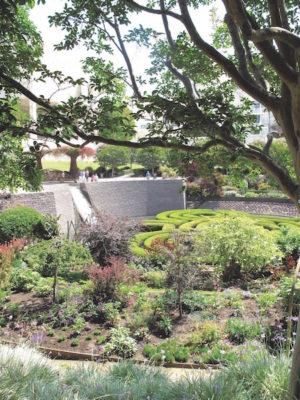

VIEW FROM Bowl Garden to Azalea Maze and waterfall, 2013.

It’s not hard to take for granted the half-century labors of artists who have made Los Angeles a star of the international art world. Robert Irwin, foremost among such artists, was asked in the 1990s to design a “sculpture in the form of a garden aspiring to be art,” as he has put it, now known as the Central Garden at the Getty Center.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, celebrating its 20th year, is the anchor of the Getty Center in Brentwood. From the beginning, the museum has ranked the Central Garden as one of its most significant pieces of contemporary art.

I am an unabashed worshipper of this sculpture in the form of a garden, with its break-all-the-rules boldness and ever-changing aspects. Irwin was hired to crack into the beautiful, rational, fresh-milk whiteness of architect Richard Meier’s shining stone village on the hill, and so he did with this exuberant work.

I learned about Irwin in 2002, when a friend lent me a copy of the film, “The Beauty of Questions.” In it, the artist keeps up a running commentary on the nature of art and perception.

“The subject of art has to do with feelings,” he says. “Art shows you the world in ways you haven’t seen it before; it brings you back to look at it again and again.”

I think this is the crux of his life’s work — how does art change your perception of the world? He has explored this question of perception (along with other Southern California light and space artists, James Turrell among them) for decades, when he gave up the idea of art, as he puts it, “encased in objects.” As he has been quoted, his art aims “to make you a little more aware than you were the day before of how beautiful the world is.”

Amen.

WATER FALLING over chert boulders, circa 2008.

It is not an exaggeration to say studying Irwin’s art and ideas — and the Central Garden at the Getty Center — have opened my world and thinking. He is a superb teacher.

A few years ago, I spent six months attending to the Central Garden once a week. The garden came to own me, and in an odd way I owned the garden. That is, I was struck by the kinesthetic and sensual experience of it — changing patterns of light cast by the carefully-plucked London plane trees; the sound of water over chunks of chert in the Stream Garden, the spray of workers’ hoses as they wade into the azalea maze; the sweet thunder of children running to see water plunging into the pool.

If you rush through a visit chattering chattering to someone else, you’ll miss it.

It became obvious that, when I see that first corner of the garden, a jewel-box of succulents, after I run down the stairs from the entry plaza level of the Getty Center, something happens — a sheer relief to be in the sight and sound and smell of all this beauty.

Gardens are the most ephemeral of the American arts, said landscape architect Fletcher Steele long ago. All I can say is: Long live this beautiful work.

Irwin’s latest large-scale work is in Marfa, Texas, part of the artist Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation, which has made the tiny west Texas town a mecca for contemporary art. Irwin’s installation-in-the-form-of-a-building has no artificial light and is reportedly beautiful, and luminous. It will be my next Irwin pilgrimage.

Irwin is quoted as asking himself — why make art here? And he answers in the same spirit that might apply to the Getty — “The sky changes. It’s amazing. Every day is a new event. The sky is everything.”

By Paula Panich

Ed. Note: The film, “The Beauty of Questions,” is not online, but many interviews with Irwin are. Details about Paula Panich’s exploration of the Central Garden can be found here: tinyurl.com/y8xbd3gk

Category: Real Estate